|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Background

|

|

|

|

The great god Zeus (zyoos), almighty ruler of creation, once fell in love with a nymph named Thetis (THEH-tis). Nymphs were minor deities, immortal like the twelve gods who lived atop Mount Olympus, but by no means as important. Thetis was one of the fifty daughters of the Old Man of the Sea. So Zeus might have thought he was paying her a compliment. But his ardor was soon quenched by a prophecy that any son born to Thetis would rule Olympus in his stead. So Zeus decided to marry off Thetis to the worthiest mortal he could find, King Peleus (PEEL-yoos) of the Myrmidons (MUR-mih-donz).

|

|

|

|

All the gods and goddesses were invited to the wedding. All, that is, but Strife. This unpopular divinity turned up anyway and lived up to her name by tossing the celebrants a golden apple inscribed "For the Fairest." Each of three goddesses strenuously insisted that it was intended for herself. These three were Hera (HEER-uh), the queen of Olympus; Athena (a-THEE-nuh), goddess of love; and Aphrodite (a-fro-DY-tee), goddess of beauty. To preserve the peace, it was decided to submit their claims to an impartial judge. And since the criterion was beauty, the designated arbiter was to be the handsomest man alive, Paris of Troy.

|

|

|

|

This Paris had been born to the Trojan royal house under ominous circumstances. The Queen, while still expectant, had a nightmare which foretold that when grown to manhood he would bring about the city's doom. The King ordered that the newborn be exposed on a mountainside. But instead of being devoured by wild animals as expected, Paris was suckled by a bear. And a shepherd, who witnessed this prodigy of nature, raised Paris as his own. He grew to be as valiant as he was handsome.

|

|

|

|

Appearing at the athletic games which the King held every year in memory of the son he had abandonned, Paris won all the contests. The King's other sons, who did not recognize their brother, were outraged to be bested by a mere commoner. But their sister, a prophetess, discerned his true identity. Thus it was as a recognized prince of the royal house of Troy that Paris resumed his shepherd's role.

|

|

|

|

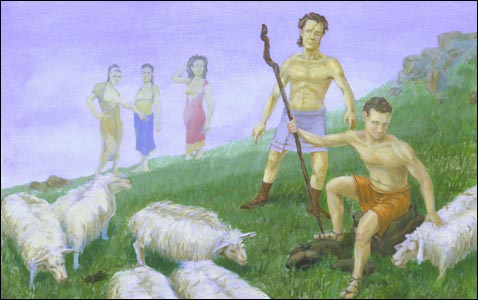

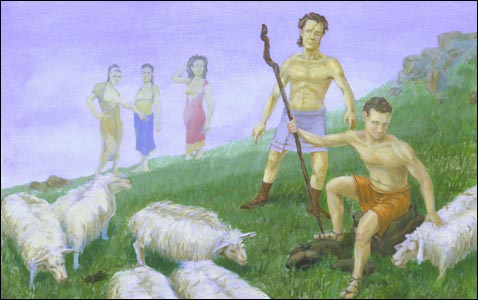

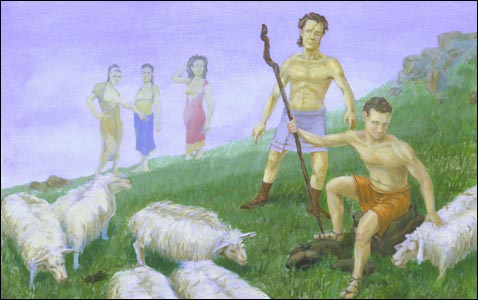

Hermes (HUR-meez), messenger of the gods, appeared to Paris as he tended his flocks on a mountainside near Troy. Once Hermes had explained the contest, he summoned the goddesses, who now revealed themselves to mortal eyes in all their glory. Not content to leave the matter to Paris's unaided judgement, each proceeded to offer him a bribe. Hera said that she would make Paris ruler of the world and rich beyond his dreams. Athena offered him victory in every battle.

|

|

|

|

Aphrodite paused to consider what might be most appealing to a young man famous for his looks. She offered him the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta — soon to become infamous as Helen of Troy. So Paris promply awarded the prize to Aphrodite. Hera and Athena just as promptly vowed to dedicate themselves to the destruction of Troy.

|

|

|

|

It did not seem to cause Paris any second thoughts when it turned out that Helen was already married. He set sail for Sparta, where he was lavishly entertained by Helen's husband Menelaus (meh-neh-LAY-us) and her twin brothers, Castor and Polydeuces (pah-lih-DYOO-sees), who had already proven themselves great heroes by such exploits as raiding Athens to retrieve their sister from fellow-hero Theseus (THEES-yoos), who had carried her off.

|

|

|

|

When Menelaus had to leave town to attend a funeral, Paris availed himself of the opportunity to elope with Helen, who had been betwitched by the Goddess of Love. He also made off with a shipload of his host's treasure.

|

|

|

|

Anxious to get his wife back, Menelaus appealed to his brother Agamemnon (a-guh-MEM-non), King of Mycenae (my-SEE-nee), who assembled a mighty fleet. (Thus Helen's was the "the face that launched a thousand ships.") A number of powerful kings had committed in advance to participate in such an effort, owing to a promise they had made to Helen's stepfather Tyndareus (tin-DAR-yoos). (Helen's actual father was Zeus himself.) When Helen had come of marriageable age, there were understandably a great many eligible suitors for the hand of the most beautiful woman in the world. Tyndareus feared the enmity of those not chosen, so he made each suitor pledge to come if called upon to the aid of Helen and whatever man she settled upon.

|

|

|

|

This strategem had been suggested to Tyndareus by Odysseus (oh-DISS-yoos) of Ithaca (IH-thuh-kuh), who came to regret it. When Agamemnon's emmissaries arrived to summon him to join the armada, he was so little inclined to go that he pretended to be mad, donning a lunatic's headgear and plowing salt into a furrow with a mismatched team. He was put to the test, however, when his infant son was placed in front of the plow. Odysseus rationally veered aside.

|

|

|

|

It was Palamedes (pal-uh-MEE-deez) who put Odysseus to this test. In another version, he simply threatened the hero's son with his sword. In any case, Odysseus had his revenge. At Troy he planted false evidence that caused Palamedes to be stoned by his fellow soldiers as a traitor.

|

|

|

|

It was this great trickster Odysseus who saw through another's scheme for avoiding conscription into Agamemnon's army. The nymph Thetis had some years previously given birth to a son with her husband Peleus. She had attempted to make the child immortal by dipping it in the river Styx (stix) in the Underworld of the dead. However, she had neglected to protect the heel by which she held it during the procedure. In any case, she was aware that her son, now grown to young manhood, was destined to die at Troy. Hoping to elude this fate, she had dressed him in girl's clothing and shipped him off to an island where he was raised as a girl.

|

|

|

|

Odysseus visited the island and had the herald sound the call to arms. It was immediately plain that one of the "girls" reacted like a proper soldier. In due course he became the greatest fighter in the Trojan War. His name was Achilles (a-KIL-eez), and he eagerly joined Odysseus.

|

|

|

|

At length the fleet was assembled but now found itself becalmed at the port of Aulis (AW-lis). A seer advised that Agamemnon had offended Artemis (AR-teh-mis), the Olympian goddess of the chase, by boasting that he was a better hunter. The fleet would never sail until its leader sacrificed his own daughter to Artemis. Reluctantly Agamemnon sent instructions to his queen, Clytemnestra (kleye-tem-NES-truh), that their daughter Iphigeneia (ih-fih-je-NY-uh) be dispatched to Aulis. Odysseus deceived the queen by saying that the girl was to be married to Achilles. On the verge of her sacrifice, Iphigeneia was snatched from the altar by Artemis, who substituted a deer and spirited Iphigeneia to barbarian Tauris (TAW-ris), where she served as priestess of the goddess.

|

|

|

|

Agamemnon's fleet set sail at last for Troy. One captain, Philoctetes (fih-lok-TEE-teez), was left behind along the way on the advice of Odysseus after he was bitten by a snake and his groans and the wound's stench became intolerable to his companions. The rest eventually found their way to Troy. As had been prophesied, the first to step ashore, Protesilaus (pro-teh-sih-LAY-us), was killed on the spot in battle.

|

|

|

|

The next nine years were spent in sacking nearby cities allied with Troy. This was necessary in order to limit supplies and assistance to the heavily fortified Trojan stronghold. It also served as a source of food, plunder, and captive women for the invaders. The first book of the Iliad begins with the consequences of one of these raids.

|

|

|

|

Notes:

|

|

|

|

elope with Helen — Some versions have it that the real Helen spent the Trojan War in Egypt under the protection of its king while a phantom Helen — made of smoke — was sent to Troy in her place.

|

|

|

|

face that launched a thousand ships — The Elizabethan dramatist Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593) was thinking of Helen when he wrote this memorable phrase.

|

|

|

|

nine years — There is a theory that it took this long to conquer Troy because the invaders were far more interested in loot. The vast riches of the Mycenaean civilization came in large part from trade but primarily from booty won in raids, wars, and the sacking of cities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|